“I demand that a film express either the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema. I am not at all interested in anything in between; I am not interested in all those films that do not pulse.”

So said François Truffaut, the renowned French director of such films as The 400 Blows and Jules and Jim. In addition to being one of cinema’s greatest artists, he was also one of its greatest patrons. Truffaut began his career as a film critic, and according to those who knew him, he had an encyclopedic knowledge of films and an unadulterated love for the filmmaking process. That love comes across in his 1973 film Day for Night, which examines the family dynamic that forms between the cast and crew of a lightweight studio film named Meet Pamela. An interesting counterpoint is Federico Fellini’s 8 ½, about a director whose long-in-development film leaves his personal life in ruin. Upon first glance, it would appear that the two films are polar opposites, but both films “pulse” with a creative energy and the joy of cinema that Truffaut was so adamant about.

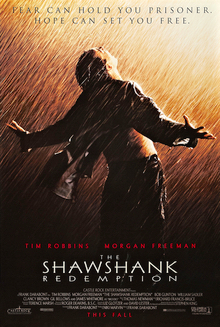

Every frame of Day for Night is bursting with love for the movie-making process. Truffaut plays Ferrand, the director of the studio comedy Meet Pamela. Jean-Pierre Leaud is Alphonse, the temperamental young star. Jacqueline Bisset plays Julie, a slightly unstable actress who has the title role in Meet Pamela. Truffaut fills out his film with other movie types – the aging supporting actress, the script girl, and various crew members.

Day for Night takes the form of a series of vignettes rather than a developed narrative, giving us a fly-on-the-wall look at life on a movie set. We observe the crew film a busy crowd scene, a car chase stunt, a simple dining room scene, and all the while we pick up on various film-making techniques. We share in the frustrations of the crew, as a cat refuses to lap up milk on cue, or as the aging actress Severine stumbles over her lines. Off set, we witness the relationships that develop among the cast and crew – friendships, romances, flings. All the while, the cast and crew are seen as a family, who share good times and console each other during bad ones.

The center of the film, though, is Ferrand, played by Truffaut as a version of himself. Truffaut once said that when he first saw Citizen Kane, he realized that he had never loved anyone as much as that film. The same would certainly be true of Ferrand, who remains doggedly fixated on making his movie above all else. To be sure, Ferrand develops friendships with his actors, and is never emotionally distant. Yet when Ferrand tries to console Alphonse after a romance gone wrong, his advice is to focus on learning his lines, because “people like you and me are only happy in our work.” That is one of the film’s strongest scenes, and it exemplifies what is so compelling about Day for Night. Not only is Truffaut’s adoration of cinema infectious, but the movie is filled with truthful human relationships.

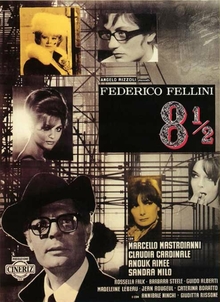

Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ is also ostensibly about the making of a movie, but it is not really a film about film in the way that Day for Night is. The protagonist of 8 ½ is Guido (Marcello Mastroianni), a celebrated director whose film and life are crumbling around him. On vacation at a resort spa along with his producers, writer, and potential stars, Guido is hounded from all sides by people who are telling him how to make his film. The truth is, Guido doesn’t know what film he wants to make, and he finds solace in drifting into his childhood memories and his fantasies, embodied by a luminous Claudia Cardinale as the wo

man of his dreams. At the same time, Guido has to compete with the real women in his life – his mistress Carla (Sandra Milo) and jealous wife Luisa (Anouk Aimee).

man of his dreams. At the same time, Guido has to compete with the real women in his life – his mistress Carla (Sandra Milo) and jealous wife Luisa (Anouk Aimee).8 ½ is remarkable on many levels. Fellini’s film weaves seamlessly between reality and fantasy, past and present without seeming at all heavy-handed. Unlike Guido, Fellini is in full command of his craft, and each segment builds upon the last to create a fuller portrait of Guido. That is not to say that every single shot or symbol makes sense. In one bizarre outdoors scene, Fellini pans past a group of characters who smile directly into the camera, and move in perfect synchronization as if they are in a sort of dance. There is no apparent reason for this, except that Fellini, ever the visual stylist, thought it looked interesting. That is not a criticism, but rather an example of how Fellini refused to follow conventions, constantly experimenting with structure and movement and composition. The film was originally titled The Beautiful Confusion, and that is exactly what it is. Even when we don’t fully understand Fellini’s intentions, his masterful direction and Gianni de Venanzo lush black-and-white photography keep the audience fully involved.

I have probably made 8 ½ sound far too esoteric, but it is really quite an entertaining movie. Fellini kept a note attached to his camera that read “Remember, this is a comedy.” Indeed, it is a rather broad comedy at times. One of the film’s most memorable sequences is a dream envisioned by Guido, who imagines a harem filled with all of the women in his life. They dote upon him, giving him baths, washing his home and preparing dinner. In another scene, Guido remembers as a schoolboy visiting the severely overweight Saraghina (Eddra Gale), a prostitute who does a grotesque and hilarious dance on the beach.

Despite these comic scenes, though, I would not generally characterize 8 ½ as a comedy. Guido spends most of the film in an unhappy state, only taking comfort in his dreams and fantasies. Only in the end does Guido find happiness, as he abandons his movie and decides to pick up the scattered pieces of his life. “Life is a celebration,” Guido tells his wife Luisa, “let’s live it together!” Fellini, unlike Truffaut, seems to be concluding that life is more important than film. And yet Day for Night and 8 ½ are not at all incompatible; both emphasize the joy of making cinema in their own way. Truffaut points out the simple pleasures of movie-making, the day-to-day gratifications of being on a set. And Fellini, through the creation of 8 ½, shows us that he is an artist of the first order, using the tools of his trade to examine the pieces of a man’s life – a beautiful confusion indeed.

Day for Night: A

8 ½: A+