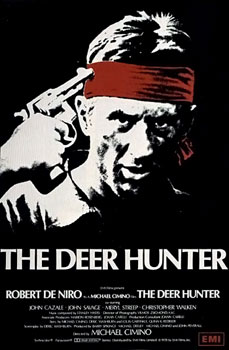

When The Deer Hunter opened in 1978, it won five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director, and was nominated in many other categories. In 1996, it was chosen for preservation by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." In 1997 and again in 2007, it ranked on the AFI's list of the top 100 American films. Indeed, The Deer Hunter is so firmly established as a masterpiece that to watch it is revelatory. The film I saw was a turgid, predictable, arguably racist film that is only somewhat redeemed by strong performances and a few memorable scenes.

Director Michael Cimino's three-hour Vietnam epic is essentially divided into three acts. The first act introduces us to a group of Pennsylvanian steel workers - Steve (John Savage), Nick (Christopher Walken), and the natural leader of the group, Michael (Robert DeNiro). The three friends celebrate a wedding and go deer hunting before they are eventually sent to Vietnam, which begins the second act. Michael, Nick, and a delirious Steve are prisoners of war, and are forced to play a game of Russian roulette. They eventually escape, but along the way Nick gets left behind. The third act of the film deals with Michael and Steve's attempt to readjust to life in America, while Nick is stuck back in Vietnam.

Each act of the film has its problems, and the first act's problem is a basic one - overlength. There is nothing particularly offensive here, but the setup is tedious, and it seems to go on for ever. The wedding scene - which reeks of an imitation of The Godfather - is a particularly good example. But we also get scenes of the friends at work, at a bar, going hunting, etc. Cimino could probably have established the friendship dynamic in half the time he uses. It is also painfully obvious where the movie is heading in the first act. When Michael promises to Nick that he will never leave him behind in Vietnam, it's obvious that that is exactly what he will do. When Michael shares a dance with Nick's girlfriend Linda (Meryl Streep), we know that they will eventually fall in love. There is very little surprise in The Deer Hunter.

The second act of The Deer Hunter, with the three friends caught in a prison camp and forced to play Russian roulette, has a reputation for being particularly harrowing and disturbing. It is not harrowing - again, it is quite clear who will or will not die during the lethal game, and the scene is curiously devoid of tension. It is disturbing, however, but for all the wrong reasons - not for the violence it depicts, but because of its depiction of the North Vietnamese. All of the Asian characters are sadistic caricatures who gleefully laugh at violence. They are stereotypes, with no sense of humanity. One can easily see why the film was deemed racist upon release, although that word may be putting too fine a point on it. Still, Cimino lacks any sense of racial sensitivity, and the film's one-dimensionality is striking. All the Americans are heroes, and all the North Vietnamese are villains. It doesn't get much deeper than that.

Admittedly, the third act of The Deer Hunter is much stronger than the first two, with many memorable scenes. There is a quietly melancholic scene where Michael returns but can't bring himself to go to his coming-home party. In another scene, Michael explodes with startling anger at his friend Stan (John Cazale), who has been joking around with a pistol. The skilled cast is most responsible for making this material work, depicting the lives of ordinary Americans who are forever shaken after the war. This is best expressed in the film's final scene, which takes place at a dimly lit dinner table after a funeral. After a long, awkward silence, one character begins to hum "God Bless America." Soon all the cast joins in, quietly singing a patriotic tune that takes on a whole new meaning. It is a powerful, darkly ironic scene.

Still, I find The Deer Hunter to be a wildly overrated film. In almost every frame, you can see Cimino straining to make a Great American Epic, but his ambition succeeds his reach. There is nothing innovative or exciting here. It's a rather simplistic film, stretched to three hours and given a reputation that it simply does not deserve.

Verdict: C+