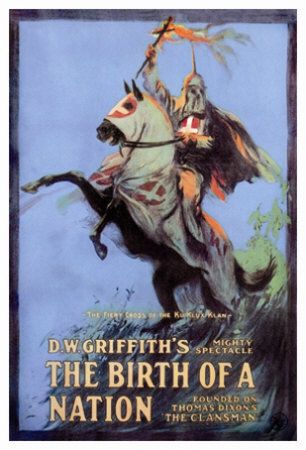

By all accounts, silent film director D.W. Griffith invented the modern feature-length film. His movies introduced ambitious storylines, editing techniques and camera tricks that had never before been seen. Yet that does not make his films any easier to watch for the modern viewer. The Birth of a Nation, Griffith's 1915 Civil War epic, is on one hand one of the most influential and important films ever made. On the other hand, it is often dry and unengaging. And of course the film is notoriously racist, playing up the worst racial stereotypes and glorifying the Ku Klux Klan as the savior of the South.

The story is split into two halves, with the first covering the Civil War and the second covering the Reconstruction period. These events are seen through the eyes of two families - the Northern Stonemans and the Southern Camerons. The families are close friends, and their relationship provides the film with its structure, as the family members witness famous events such as Lincoln's assassination and the rise of the KKK.

So just how racist is The Birth of a Nation? Well, the film certainly anticipates its criticism, with a disclaimer at the beginning saying that the story is not supposed to reflect any race of today. And given all that I had read, I was expecting worse during the film's first half. The racism is certainly there - all of the slaves are portrayed as being perfectly happy, and black soldiers are portrayed as mindless followers - but the first half of the film does not actively condemn blacks, preferring to tell its war story.

However, all of that completely changes in the second half. Part two opens with a quote from Woodrow Wilson that glorifies the Ku Klux Klan, calling it "a veritable empire of the South" that arose "to protect the Southern country." Black characters (most of whom are played by white actors in blackface) are seen as villains who overtook the South and trampled on its great legacy. In one scene at the State House of Representatives, there is an overwhelming majority of blacks, and they are all portrayed as uncivilized and incompetent. A caption card laments the "helpless white minority." In the next scene, Ben Cameron is inspired to create the Ku Klux Klan, who are seen as the film's heroes. In yet another scene, a black character named Gus attempts to rape young Flora Cameron. He is later executed by the KKK. These are just a few examples of the racism in the film.

So yes, The Birth of a Nation is morally despicable. But is it watchable? For the most part, I found the film to be tedious and overlong. Unlike The Passion of Joan of Arc, another silent film that I reviewed, it does not stand well on its own merits. If one puts aside the racism and the cinematic importance, The Birth of a Nation is simply not very engaging. There are a few notable exceptions, though. The assassination of Lincoln is very suspenseful, and a few battle scenes are exciting.

Still, how can I possibly hold that against the film? The Birth of a Nation is in many ways the birth of cinema, and it is unfair to criticize its narrative for not being fully developed. It would be like looking back and criticizing Edison's lightbulb for not being bright enough. With that in mind, I begin to see the folly of assigning any sort of rating to this film. Can I possibly judge The Birth of a Nation the same way I would judge, say, Quantum of Solace? Of course not. It may be that I am simply not knowledgeable enough about silent film to fully appreciate the movie. Suffice to say that The Birth of a Nation is not an easy film to watch, due to both its nature as a 3-hour silent film and its outspoken racism. But it is undeniable that it is a film of lasting historical importance, and should be viewed as such.