Nicholas Ray never won an Oscar or a lifetime achievement award, worked in Hollywood for little more than a decade, and directed only a few canonized classics. His most famous film, Rebel Without A Cause, is remembered for James Dean's iconic performance rather than Ray's direction. Surprising, then, that this was the man whose career launched the auteur theory. François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, and Jean-Luc Godard sang his praises in the pages of Cahiers du Cinéma, seeing in his work the possibilities of a newly personal cinema, in which the director was the true author of the movie. When these same critics became filmmakers themselves, and the leaders of the French New Wave, they continually cited Ray as a formative influence. Godard even dedicated his film Made in U.S.A. to Ray, and once declared, in typically hyperbolic fashion, "The cinema is Nicholas Ray!" All this while Ray was ignored in his native land.

Nicholas Ray never won an Oscar or a lifetime achievement award, worked in Hollywood for little more than a decade, and directed only a few canonized classics. His most famous film, Rebel Without A Cause, is remembered for James Dean's iconic performance rather than Ray's direction. Surprising, then, that this was the man whose career launched the auteur theory. François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, and Jean-Luc Godard sang his praises in the pages of Cahiers du Cinéma, seeing in his work the possibilities of a newly personal cinema, in which the director was the true author of the movie. When these same critics became filmmakers themselves, and the leaders of the French New Wave, they continually cited Ray as a formative influence. Godard even dedicated his film Made in U.S.A. to Ray, and once declared, in typically hyperbolic fashion, "The cinema is Nicholas Ray!" All this while Ray was ignored in his native land.What, exactly, makes Nicholas Ray an "auteur?" Upon first glance, he might seem merely a workmanlike, efficient Hollywood director. Unlike his French admirers, Ray was never really an independent filmmaker, rather working under the confines of the studio system. Neither did he specialize in a particular genre, but rather dabbled in film noir, Westerns, Biblical epics, socially conscious dramas, adventure films, and more. But Ray's triumph was to make deeply personal films with popular appeal. Each of his films, no matter the genre, is graced with the same qualities: a dynamic and expressionistic visual style, and a thematic concern for the lonely and isolated. Ray's films also address societal issues like suburbanization, the Communist witch hunts, and environmentalism - themes that were overlooked at the time but which only make his movies more fascinating as time goes by.

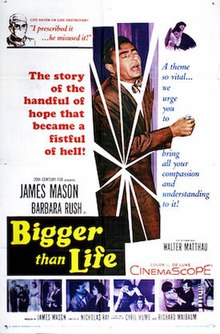

Bigger than Life (1956) is perhaps Ray's masterpiece. The story could almost be an after school special: a suburban father begins taking an experimental drug, which dramatically transforms his personality and nearly destroys his family. In the end, though, he recovers, repents, and the happy family is reconciled. Under another director, Bigger than Life could have been an insufferable message movie. Instead, though, Ray uses this plot to launch a freewheeling critique of American society in the 50s. We begin to understand that Ed Avery, the main character played by James Mason, is not fundamentally changed by the drug - it merely unleashes his suppressed feelings about his life, his family, and his culture. The failings of American education, the obsession of consumerism, the banality of suburban life, the superficial distinctions of class, the realities of a loveless marriage - all are targeted in Bigger than Life.

Part of what makes Ray a great director is his ability to dramatize his themes visually, and Bigger than Life is perhaps the best example. The film is shot in the aspect ratio of 2.55:1, an extremely wide format that allows Ray to fill the frame with revealing details. Consider the way Ray films Avery's house. The house is a typical specimen of suburbia, and would not be out of place in Leave it to Beaver or Father Knows Best. As the film progresses, though, the house becomes a visual representation of Avery's character, an extension of his psyche. The walls of the house are plastered with posters of European cities that Avery will never visit. A deflated football on the mantelpiece is a sad reminder of his fading college football days. The spacious interiors and separation of rooms suggest the estrangement that Avery feels from his family.

Ray, who made some of the great film noirs, is certainly no stranger to shadows. In Bigger than Life, they are everywhere. Initially, most of the interiors are shot with muted colors and low light, but Ray ups the contrast later in the film, setting bright colors against dark shadows. Consider the shot below, in which Avery looms over his son, pressuring him to finish a math problem. So many themes of the movie are present in that one shot: the impossible expectations Avery sets for his son, the God complex that the use of cortisone has given him, the ugly demons that overtake his personality. And perhaps above all, Richie, the son, isolated in the foreground, overwhelmed and silently crying.

Richie, in fact, may be the key to the film. Upon a second viewing, it struck me that the viewer's sympathies - and certainly Ray's - lie almost entirely with this little boy. Richie is the wisest character in the film - the first to notice the effect of the drug on his father, the first to question his father's newfound obsession with spending money, and ultimately the one to call the doctor and make his father stop taking the pills. But Richie's mother dismisses his concerns, and his father considers him a failure. "Childhood is a congenital disease, and the purpose of education is to cure it," Avery says at one point. In the end, Avery gives up on even this cynical mantra, deciding to sacrifice his son in an imitation of Abraham slaughtering Isaac. Until a deus ex machina appears, of course, saving Richie and delivering a happy Hollywood ending.

Richie, in fact, may be the key to the film. Upon a second viewing, it struck me that the viewer's sympathies - and certainly Ray's - lie almost entirely with this little boy. Richie is the wisest character in the film - the first to notice the effect of the drug on his father, the first to question his father's newfound obsession with spending money, and ultimately the one to call the doctor and make his father stop taking the pills. But Richie's mother dismisses his concerns, and his father considers him a failure. "Childhood is a congenital disease, and the purpose of education is to cure it," Avery says at one point. In the end, Avery gives up on even this cynical mantra, deciding to sacrifice his son in an imitation of Abraham slaughtering Isaac. Until a deus ex machina appears, of course, saving Richie and delivering a happy Hollywood ending.Despite this obvious compromise, Bigger than Life remains perhaps Ray's greatest film: a social satire posing as a domestic melodrama that becomes something of a horror film. It is a movie of ideas, but these ideas never overtake the film's emotional center - Richie. He stands for his entire generation, I think, and he shares some affinities with the hero of Ray's previous film - James Dean's Jimmy Stark. It is easy to see how Richie, too, could become a rebel without a cause.

How to describe Johnny Guitar (1954)? François Truffaut put it this way: "It is dreamed, a fairy tale, a hallucinatory Western...Johnny Guitar is the Beauty and the Beast of Westerns, a Western dream. The cowboys vanish and die with the grace of ballerinas." That oft-quoted description comes close to capturing the film's wonderful strangeness, its bizarre remove from its own genre. Here is a Western where the gunslinger is a mopey, laid-back guitar player who hardly influences the action at all. The real drama, and indeed the final shootout, is between two women: Joan Crawford's Vienna, a saloon owner who is being run out of town, and Mercedes McCambridge's Emma, a Puritanical cattle rancher who wants her gone. The ostensible cause of the women's enmity is the love of a man, but the film is rife with barely concealed lesbian tension. "I never met a woman that was more man," a bartender says of Vienna, and Emma seems oblivious of all men in her quest to bring down Vienna.

How to describe Johnny Guitar (1954)? François Truffaut put it this way: "It is dreamed, a fairy tale, a hallucinatory Western...Johnny Guitar is the Beauty and the Beast of Westerns, a Western dream. The cowboys vanish and die with the grace of ballerinas." That oft-quoted description comes close to capturing the film's wonderful strangeness, its bizarre remove from its own genre. Here is a Western where the gunslinger is a mopey, laid-back guitar player who hardly influences the action at all. The real drama, and indeed the final shootout, is between two women: Joan Crawford's Vienna, a saloon owner who is being run out of town, and Mercedes McCambridge's Emma, a Puritanical cattle rancher who wants her gone. The ostensible cause of the women's enmity is the love of a man, but the film is rife with barely concealed lesbian tension. "I never met a woman that was more man," a bartender says of Vienna, and Emma seems oblivious of all men in her quest to bring down Vienna.The plot is patently ridiculous, the colors are outlandish, and the film has few of the traditional pleasures of the Western. It's easy to see, then, how Johnny Guitar has become something of a cult classic; it's also easy to see how it could be dismissed as little more than an eccentric example of genre revisionism. But the movie is better than that. Despite all of its ludicrous trappings, the true story of Johnny Guitar is a sincere, affecting one. It reiterates Ray's perpetual themes of loners and outsiders. Vienna is a woman hardened by life and unrequited love, who builds her saloon as a kind of haven. Johnny is a wanderer who returns to his ex-lover, Vienna, for a few days of happiness before Emma's posse descends on the saloon and ruins their paradise.

Johnny Guitar is also an unapologetic commentary on McCarthyism and the Hollywood blacklist. About halfway through the film, Sheriff McIvers (Ward Bond) is desperate to frame someone for the robbery of a stagecoach, and his gang try to make townspeople testify against each other - a clear parallel to the House Un-American Activities Committee and their attempts to root out suspected Communists. The issue would certainly have had personal significance to Ray. His political views leaned towards the left, and many of his closest collaborators - among them Johnny Guitar's screenwriter Ben Maddow, and Humphrey Bogart - had been targeted by HUAC. Ray dresses the sheriff's gang in matching black, and arranges them in diagonal formations that suggest their gang mentality.

What emerges from Johnny Guitar most clearly, though, apart from these political overtones, is a sense of doomed romanticism. Ray's vivid use of color and space, the melancholic score, and the script's surprisingly moving romantic exchanges do indeed create a dreamlike quality, as suggested by Truffaut. This is not a hard-hitting Western, but a sensitive, passionate one, in which the characters all seem to be wounded and yearning for love.

What emerges from Johnny Guitar most clearly, though, apart from these political overtones, is a sense of doomed romanticism. Ray's vivid use of color and space, the melancholic score, and the script's surprisingly moving romantic exchanges do indeed create a dreamlike quality, as suggested by Truffaut. This is not a hard-hitting Western, but a sensitive, passionate one, in which the characters all seem to be wounded and yearning for love. Wind Across the Everglades (1958) is obscure even by Ray's standards. It was never released on VHS, let alone DVD, and its two main stars were hardly A-listers: Burl Ives and Christopher Plummer. What's more, it has to be asked if it is a Nicholas Ray film at all. The movie was the brainchild of screenwriter Budd Schulberg, and was produced by his brother Stuart; when they were unhappy with Ray's style, they fired him and Budd directed the rest of the film. The critic Jonathan Rosenbaum has described it as "a kind of litmus test for auteurists," and from that perspective it is a fascinating case study.

Wind Across the Everglades (1958) is obscure even by Ray's standards. It was never released on VHS, let alone DVD, and its two main stars were hardly A-listers: Burl Ives and Christopher Plummer. What's more, it has to be asked if it is a Nicholas Ray film at all. The movie was the brainchild of screenwriter Budd Schulberg, and was produced by his brother Stuart; when they were unhappy with Ray's style, they fired him and Budd directed the rest of the film. The critic Jonathan Rosenbaum has described it as "a kind of litmus test for auteurists," and from that perspective it is a fascinating case study.Unfortunately, and perhaps inevitably, the movie itself is somewhat choppy. Schulberg so resented Ray that he threw away much of his footage, and the narrative is not easy to follow. The story is set in early 19th century Florida, and concerns a game warden (Christopher Plummer) who comes to enforce conservation laws and goes up against a violent bird poacher (Burl Ives). There is also a romantic subplot that goes nowhere.

Wind Across the Everglades plays like a rough draft of a film that, if polished, could have become something much greater. Nonetheless, the movie is not without interest. For a 1958 film, it is curiously modern in its depiction of the environment. The opening scene depicts, in a documentarylike fashion, how the whims of women's fashion nearly decimated the population of birds in Florida. The main character, moreover, is a strident conservationist who pits himself against a ruthless hunter. The relationship between these two men is the core of the film. Both men are, in their own way, outcasts from society. Despite their professional differences, the two men unite over a drinking game, in an extended scene that seems spontaneous and improvised. Alas, such improvisational techniques are what got Ray fired from the film.

Wind Across the Everglades is less than the sum of its parts, but in some scenes Ray's brilliance is clearly evident. Ray's visual gifts are on full display, though this time he largely trains his camera on beautiful wildife exteriors, as opposed to the interiors of Bigger than Life and Johnny Guitar. A subplot involving a Native American is a classic example of Ray's outsider theme, and the performances he coaxes from the actors are uniformly strong. One only wishes that Ray had been allowed to see his vision through from beginning to end.

What makes a great director? For the famous critic Andrew Sarris, it was the presence of a theme. For Orson Welles and the New Wave critics, it was the extent to which the work represented the man who made it. Others might point to style, or influence. Whatever the criteria, Nicholas Ray seems to have it all.

Apologies for the delay with this post! When I saw these films in July at the Harvard Film Archive, I never expected that it would take 5 months to write the blog post on them. Hopefully, with my college apps almost done, I will have more time for blogging in the future.