In September 1958, an advertisement appeared in the French newspaper France-soir for a thirteen year-old boy to play the lead role in an upcoming feature film, The 400 Blows. The director was known in some circles for his controversial film criticism, but had never before directed a feature. The actor eventually chosen was also an amateur, and was initially deemed too old for the part. Yet these two men, Francois Truffaut and Jean-Pierre Léaud, forged a creative partnership and friendship that would last for decades. Incidentally, they also made one of the cornerstones of cinema, a film that kickstarted the French New Wave and ushered in a new era of personal filmmaking.

Looking back today, it hardly seems possible for it to have happened any other way. Rarely has there been such a perfect harmony between actor and director, with each man's personality equally informing the character of Antoine Doinel, who evolved in four sequels. The 400 Blows, rightly, is the most admired, but none of the later Doinel films is without value, and they all play off of motifs established in the first film.

In The 400 Blows, Antoine is a 13 year-old living in Paris with a stressed-out mother and distant stepfather. Neglected at home and vilified by his teacher at school, Antoine spends much of his time wandering through Paris with his friend René - going to movies, carnival rides and parks. Due to a series of poor decisions and misunderstandings at home and school, Antoine resorts to petty crime, and is sent to a seaside camp for juvenile delinquents.

Truffaut said his goal was "not to depict adolescene from the usual viewpoint of sentimental nostalgia, but....to show it as the painful experience it is." His visual style fits the mood - the films is shot in gritty black-and-white, set in cramped apartments, crowded prisons and dirty playgrounds. But the film also captures the excitement of living in the city, the simple pleasures of going to the movies and exploring the city with friends. In one sequence, Antoine goes on a centrifugal carnival ride, and ends up suspended in midair, back against the machine as it spins around. Adults watch from a distance, but Antoine can hardly make them out. It is a striking scene, and one that emphasizes Antoine's uncertain place in the world - stuck between childhood and the world of adults who don't seem to understand him.

Then there is the final scene, one of the most famous in cinema. It shows Antoine as he escapes from his juvenile holding camp. For a few minutes, Truffaut just shows us Antoine running, as he seems to do so often in the series. Then, an exhausted Antoine sees the sea for the first time, wades into the water, and turns to face the audience. The film ends with a zoomed-in freeze frame of Antoine's face. This shot, in some ways, is a miniature of the entire film - an honest, unflinching look at adolescence, freed from all sentimentality and false artifice.

Of all the sequels, Antoine and Colette looks most like The 400 Blows, but announces a departure in terms of tone and mood. This time, Antoine is not an angsty, misunderstood adolescent but a plucky 19 year-old working at a record store in Paris. Antoine is also a regular conertgoer, and it is at one such conert that he meets Colette (Marie-France Pisier), who soon becomes the object of his affections. Antoine tries to woo her, but only manages to charm her parents.

Antoine and Colette (a 30-minute short originally made for the omnibus Love at Twenty) seems downright lightweight compared to The 400 Blows. It maintains the previous film's black-and-white photography and Parisian settings, but the tone is more comic and romantic. That does not mean it is a bad film, for it is certainly an acute and bittersweet portrayal of young love. But it is an intermediary film more than anything, and perhaps too short to fully establish itself.

The romanticism of Antoine and Colette is taken even further in the next installment, Stolen Kisses. This time around, Antoine has been dishonorably discharged from the army, and finds himself on the streets of Paris looking for a job. He eventually finds one in a private detective agency. He also finds love, in the form of an older married woman (Delphine Seyrig) and a charming girl his own age, Christine (Claude Jade).

The romanticism of Antoine and Colette is taken even further in the next installment, Stolen Kisses. This time around, Antoine has been dishonorably discharged from the army, and finds himself on the streets of Paris looking for a job. He eventually finds one in a private detective agency. He also finds love, in the form of an older married woman (Delphine Seyrig) and a charming girl his own age, Christine (Claude Jade).Stolen Kisses is light, funny, somewhat episodic and mostly irresistible. The success of the movie lies not so much in Truffaut's mise-en-scène but in the charms of the characters and script. It is also the film where Léaud, so arresting as the troubled boy of The 400 Blows, emerges as a full-fledged comedic actor. By this point in the series, you can see how the character evolved from a distillation of Truffaut's troubled childhood to a combination of Truffaut and Léaud's sensibilities. At its most basic level, though, Stolen Kisses is a skillful romantic comedy- whimsical, sentimental, slightly forgettable, but hard not to enjoy.

Bed and Board is my sentimental favorite of the Doinel series, though my perceptions of it are no dobut colored by the circumstances in which I first saw it. I saw both Bed and Board and Love on the Run as a double feature at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge. As someone largely raised on VHS and DVD, seeing a real film print of a cinema classic is truly a thrill that cannot be replicated at home. In any case, though, there is something more about Bed and Board that makes it rise above the other Doinel sequels. The first half of the film is a domestic comedy that resembles Stolen Kisses in its episodic nature and comedic tone. Much of the film is set in a courtyard where Antoine works selling flowers; his wife Christine works as a violin tutor in their apartment a few floors above. Through a series of vigenttes, Truffaut establishes the supporting characters - a moocher who is constantly asking Antoine for money, a woman who is always hitting on him, a silent, shifty-eyed man deemed "The Strangler" by the apartment residents.

Bed and Board is my sentimental favorite of the Doinel series, though my perceptions of it are no dobut colored by the circumstances in which I first saw it. I saw both Bed and Board and Love on the Run as a double feature at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge. As someone largely raised on VHS and DVD, seeing a real film print of a cinema classic is truly a thrill that cannot be replicated at home. In any case, though, there is something more about Bed and Board that makes it rise above the other Doinel sequels. The first half of the film is a domestic comedy that resembles Stolen Kisses in its episodic nature and comedic tone. Much of the film is set in a courtyard where Antoine works selling flowers; his wife Christine works as a violin tutor in their apartment a few floors above. Through a series of vigenttes, Truffaut establishes the supporting characters - a moocher who is constantly asking Antoine for money, a woman who is always hitting on him, a silent, shifty-eyed man deemed "The Strangler" by the apartment residents.But about halfway into the movie, the tone changes as Antoine begins an affair with a Japanese woman. Up until this point in the series, the movies have relied on the natural likability of the main character. Now the empathy switches to Christine, and Truffaut portrays Antoine as a boy who refuses to grow up. In the centerpiece of the film, a separated Antoine and Christine have a passionate discussion which rapidly changes from a heated argument to a declaration of love. At one point, Christine lashes out against Antoine's desire to have everything his way. On the subject of Antoine's autobiographical novel, she says that "if you use art to settle accounts, it's no longer art." You can almost hear Truffaut's doubts in that statement; he seems to be questioning the artistic value of the entire series. At the very least, he seems fed up with playing the story for laughs, and Bed and Board briefly regains the melancholy tone that made The 400 Blows so powerful.

Consider the end of the scene. A cab arrives to take Christine into the city for a night of shopping. Before she leaves, she senses that Antoine is lonely and asks if he wants to go to a movie. After a few minutes of joking around, Christine gets in the cab and asks Antoine to kiss her, although they have already established that they will not be seeing each other. He does, and in typically melodramatic fashion declares, "You're my little sister, my daughter, my mother." Christine responds with an understated "I'd have liked to be your wife too."

This scene alone reveals what a terrific writer Truffaut was; it is an emotional rollercoaster ride in which the confused emotions of the main characters keep bubbling to the surface, threatening to obscure their best intentions to stay away from each other. It may be true, as it is frequently claimed, that by this point in his career Truffaut had abandoned the experimental, avant-garde nature of his early work for a more traditional style. But he never gave up the humanism that made his work so moving and so accessible to so many people. There are no flashy camera tricks or showy editing techniques in Bed and Board. It is purely minimalist, and extremely effective at that. All that needs to be said about Antoine's regret is shown in the shot where Christine's cab pulls away and Antoine walks down a lonely street into a brothel.

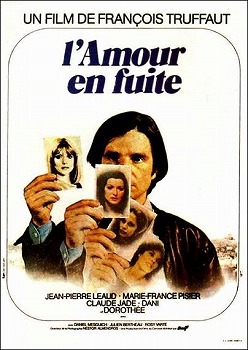

Bed and Board was originally intended to be the final Antoine Doinel film, and in retrospect it probably should have been. At times, Love on the Run seems like a clipshow; it features numerous flashbacks to all the previous films, which only makes it seems slight in comparison. It also seems altogether too tidy, with every aspect of Antoine's life coming together to create a happy ending. Finally, Love on the Run is a retreat from the serious reflection of Bed and Board, reverting back to the comedic situational comedy of Stolen Kisses.

Bed and Board was originally intended to be the final Antoine Doinel film, and in retrospect it probably should have been. At times, Love on the Run seems like a clipshow; it features numerous flashbacks to all the previous films, which only makes it seems slight in comparison. It also seems altogether too tidy, with every aspect of Antoine's life coming together to create a happy ending. Finally, Love on the Run is a retreat from the serious reflection of Bed and Board, reverting back to the comedic situational comedy of Stolen Kisses.The film is helped a great deal by the return of Colette's character; the actress Marie-France Pisier infuses the film with much-needed warmth. The style of the film is also noteworthy - the editing is quick and forceful, featuring swift cutaways and fast zooms. But the story is ultimately where the film falls apart. Antoine's love interest, Sabine, hardly establishes a personality of her own, and there is a genuine lack of new, interesting material.

Despite the final film's shortcomings, the Antoine Doinel series really is a remarkable piece of work. It is too easy to dismiss the sequels to The 400 Blows as sentimental fluff, but this is simply not the case. Watching the entire series, you can trace the evolution of Antoine Doinel not only in terms of plot, but in the sensibilities of his creators. You can also see the whole series as an examination of the fine line between adolescence and adulthood. Or you can simply get caught up in the story, in the acute feelings that Truffaut's films so effortlessly exude. No matter how you look at it, The Adventures of Antoine Doinel is a success.

Ratings (out of 4 stars)

The 400 Blows: ****

Antoine and Colette: ***

Stolen Kisses: ***

Bed and Board: ****

Love on the Run: **1/2